ATC

Digital Textbooks and the Future

About Us

Publications & Reports

Contact Us

Widely Adopted History

Textbooks

Senate Testimony

Review Guidelines

Islam in the Classroom

What will be the impact of digital technology on instructional materials and instruction? Hardware in the classroom already shows itself to be distracting. Dartmouth computer studies professor Don Rockmore writes in the New Yorker on "The Case for Banning Laptops in the Classroom."

Twenty years ago, some educators were convinced that all textbooks would soon all be on floppy disks and desktop monitors.

No wonder educators and school district business managers fear committing their classrooms to hard-to-replace, costly instructional hardware and software that could soon be obsolete. Do students today even know what floppy disks are?

In the future some electronic lessons will be purchased. Others will be “open source.” That means they will be free and available online to anyone. Who will pay for open-source instructional materials development is a profoundly important and unsettled question.

Pearson, McGraw-Hill, and Harcourt Houghton Mifflin hope that school districts will pay money to license and use their electronic, downloadable lessons. Publishers already provide elaborate electronic support for districts and teachers who buy their printed texts.

Open-source is a serious threat to traditional educational publishing. Forward-looking foundations and individual professors have produced lessons and study packages that match or exceed what established publishers offer.

Enterprising teachers can already access a vast number of outstanding instructional materials, including databases from the National Endowment for the Humanities and National Academy of Sciences. Most teachers are not so enterprising, and school publishers depend on this inertia to survive. Multi-media are extremely expensive to create. If developers want to reproduce the look of a zippy, colorful, fast paced television show, their costs will be high.

Discovery Education, a Maryland-based cable media company with no background in textbook publishing, has tried to turn audio-visual streaming programs into a coherent instructional package. It has obtained state approval for its digital science programs several states.

Lack of realism about technology and its capacities takes many forms. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan and former California state education board president Reed Hastings wrote a 2011 opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal equating the productive advantage of computers in the workplace to the classroom, ignoring glaring differences between the two. A perceptive review by Michael Hiltzik that followed in the Los Angeles Times demolished this illogical, magical thinking.

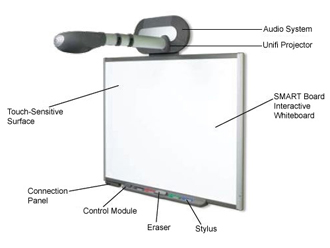

The most prevalent computer-based instructional device in classrooms today is the large-scale electronic whiteboard, especially popular and sought after among elementary-school teachers for whole-class lessons. Promethean is one well-known brand name. SmartBoard is another.

These big-screen, thin-line monitors allow instructors to project everything from PowerPoint text to super-graphics, multimedia, and interactive problems on the big screen. The 4x8 foot screen can double as an interactive, electronic “blackboard” that a teacher can write on. Prometheans and SmartBoards are computer-driven overheads, costing some $2,000 and up. New schools and rich schools are wiring them into classrooms.

Software companies - the unbearably named Cookie Company is one of them - are content providers, favoring the glossy and slick, avoiding complex or serious topics, problem sets, and language arts. Some, many taste notches below Discovery Education, sell break-dancing chipmunks that “teach” multiplication and bunny rabbits asking children to recite slogans to convince themselves that everybody’s special.

Digital textbooks are made possible by the use of electronically driven tablets or laptops - expensive and fragile, risky and sometimes short-lived in the hands of children and teenagers - or with less portability and access, by media centers in schools.

Such instructional materials can range from printable online text - a downloadable textbook -- to a web-based interactive curriculum with kinetics, streaming, multimedia and links.

It’s all marvelous, the electronics and multimedia, except for one crucial thing. The blinking lights and ravishing color may discourage concentration. In comparison to old media, digital formats may not be conducive to learning and ingesting facts, reading carefully, contemplation, or lengthy reflection. They may discourage serious learning.

Big-screen lessons and PowerPoint invite us to lower the bar between serious learning and entertainment.

How can we fail to notice that many classroom lessons, especially in audio-visual and overhead format, resemble cartoon entertainment and video games? At the lower end of the educational ladder the main job of teachers is to keep incapable and easily distracted children occupied, thus preventing unruly or anti-social behavior.

Many teachers already overuse audio-visuals to fill the day. Whiteboard “lessons” - like the once ubiquitous, now nearly extinct television monitor and VCR -- provide easy-access, in-class, group entertainment. Many instructors design lessons that depend on what SmartBoards can do. They will be tempted to use them even more if books and pen-and-paper continue to vanish from classrooms.

Electronic lessons open up a world of learning - if students get to the right sites and the right content. There is solid, sometimes dazzling, open-source material available online and more to come each year. The trouble is getting teachers, locked into standards and tests, to go there. Quality-conscious parents understand what educators don’t like to admit. The dancing chipmunks are winning more than a few faculty hearts and minds. They are asking all of us to sing along.

Many skeptical teachers still say that books work in class with a minimum of fuss. What printed textbooks have going for them are convenience, familiarity and reliability. Books do not require a power source or expensive hardware. Glare and washout from backlit screens in bright light present serious practical problems. (That’s why the Kindle-like electronic paper format is easier to read than an iPad.)

Books are not exactly cheap, but they often get considerable mileage, lasting for years, thus giving good value. Many students like the feel and solidity of a book. Watch students using a printed textbook and they are often thumbing around, turning pages. Books allow them to navigate pages, flipping from tables of contents to index with an ease that iPads and Kindles cannot match.

High-minded educational software designers concede that electronics and multimedia dampen enthusiasm for sustained text-only reading. But few educational software designers are high-minded. They are mercenary in intent. Americans of all ages are growing impatient with slow-motion printed narrative. But those under 35 - and that includes newish teachers - are supremely comfortable with electronic media and turn to them, not books, as instructional inspirations. They like pictures and kinetics, not uninterrupted, tedious, black-and-white text.

The matter of equity is equally – some would say more -- disturbing. Affluent, tech-savvy private schools and parents who at once “get” technology and provide a literate counterpoint to the electronic world that children inhabit give learners an incalculable advantage going forward.

Emory University English professor Mark Bauerlein makes a strong case that digital learning stupefies students and jeopardizes knowledge. Oxford neuroscientist Susan Greenfield suggests that social networking websites, computer games, and electronic media shorten attention spans, inhibit absorption, and make young people more self-centered. Bauerlein warns of a catastrophic retreat of knowledge and serious study. Inside and outside of classrooms, can Americans resist the tinsel and keep the content bar high? Or are superficial learning and high-tech “attention deficit disorder” inevitable and already epidemic?

What thoughtful teacher, psychologist or cleric is entirely happy about electronics’ impact on community and individual feeling? Who doesn’t wonder where the pixels will take us as a nation and people?

Educators have a good idea what we should guard against, but we don’t know if we have the inner tools of resistance.

© 2014 Gilbert T. Sewall

Home | About Us | Publications & Reports | Contact Us

Widely Adopted History Textbooks

Senate Testimony | Review Guidelines |

Islam in the Classroom | Digital Textbooks

Widely Adopted History Textbooks

Senate Testimony | Review Guidelines |

Islam in the Classroom | Digital Textbooks

Copyright © 2021. American Textbook Council. All Rights Reserved.